A European Venus mission risks missing its launch window due to ongoing squabbles over the NASA budget.

The American space agency is supposed to provide a key instrument for the probe, intended to conduct a comprehensive investigation of the Venusian geology and the planet’s fiery atmosphere. Funding for development is among the many projects proposed for elimination by the Trump administration, which has thrown mission progress into uncertainty just as work needs to proceed toward construction milestones to make the tight deadline.

The mission, called EnVision, which began development in January 2025, is one in a string of fraught science partnerships between NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA), prompting some European scientists to call for a re-evaluation of future collaborations.

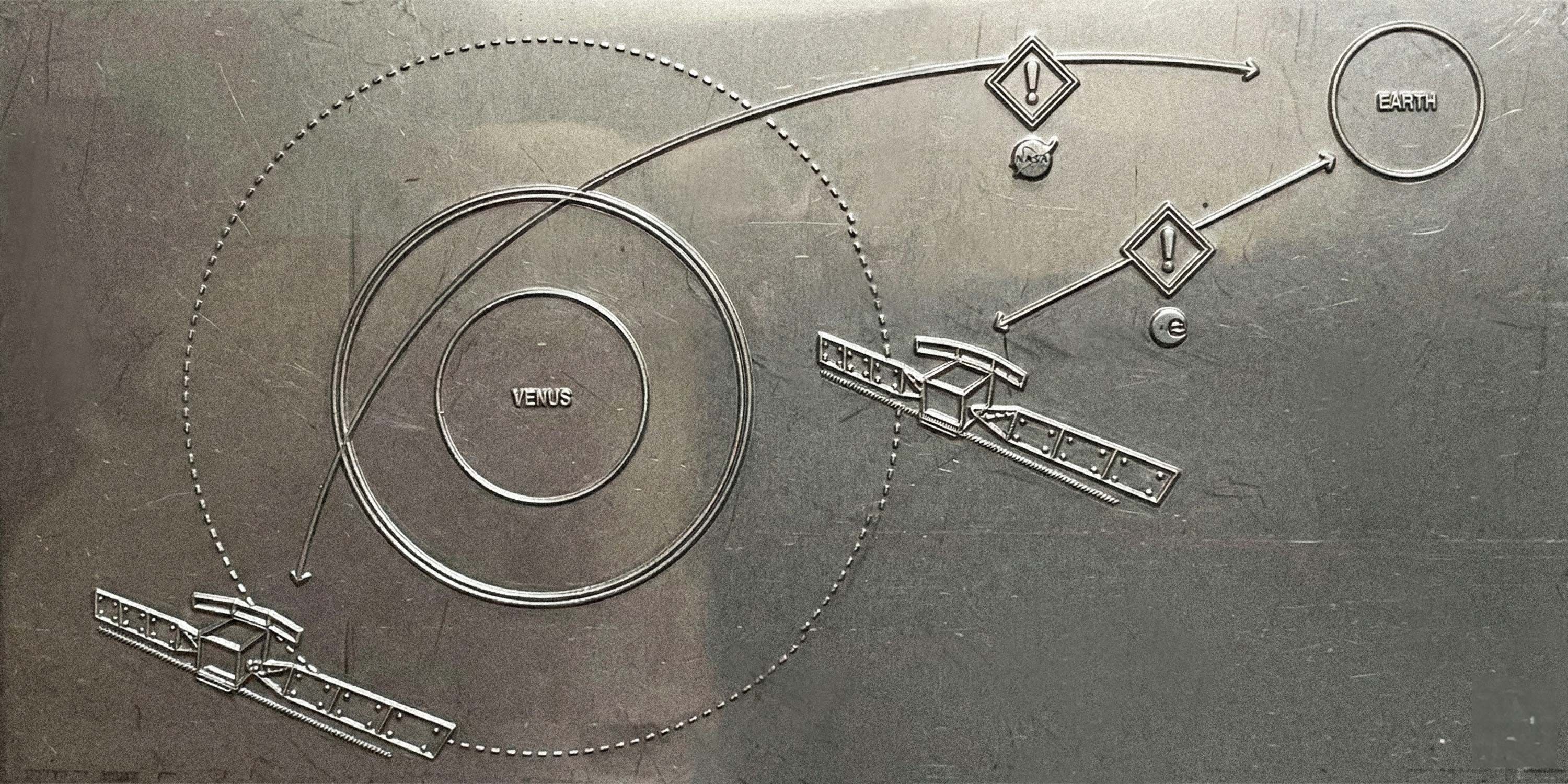

The 4-metric-ton EnVision probe, being built by the Franco-Italian conglomerate Thales Alenia Space, must take off for its 15-month journey to Venus in 2032, otherwise it will miss the favorable planetary alignment that will only re-occur in 2036.

The NASA-made instrument, called VenSAR, is a powerful synthetic aperture radar designed to map the planet’s surface in three dimensions and with an unprecedented resolution of up to 10 meters per pixel.

Although the Trump administration proposed to scrap the VenSAR development, the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate intend to reinstate at least some of the funding. As of early December, the NASA 2026 budget has not been finalized. Time is, however, ticking for EnVision. ESA has already began looking for European alternatives for VenSAR, but if the wait for NASA’s decision keeps dragging on, the European party may end up not having enough time to build the innovative radar.

“It might be necessary to cut NASA out in the new year if no decision will have been made or sufficient guarantees are not forthcoming, since the risk to the mission of NASA pulling out later are too great,” a source familiar with the history of the EnVision collaboration who wished to remain anonymous, told Supercluster.

A String of Let-Downs

EnVision is just one in a string of joint ESA-NASA science and space exploration partnerships hanging in limbo because of the changing U.S. priorities.

ESA says that 19 joint space science missions plus Europe’s first Mars-bound rover ExoMars will suffer funding shortfalls or face cancellation under the Trump administration's plan. Among them is the space-based gravitational wave detector LISA (the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna), a planned constellation of three identical spacecraft detecting ripples in spacetime triggered by collisions of black holes and neutron stars.

NASA committed to providing high-tech equipment for LISA worth up to $1 billion, according to the Planetary Society, a non-profit organization advocating for space exploration. But, ESA has already began looking for options to source this technology — onboard lasers and telescopes — in Europe.

Guido Mueller, a professor of precision interferometry at the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Wave Physics in Germany and a member of the LISA science consortium, told Supercluster that European companies should be able to deliver the high-tech systems with only about a two-year delay to the mission’s currently planned 2035 launch date. That is if they are given the green light to proceed soon enough. But ESA has not officially parted ways with NASA yet.

Like EnVision, the European agency keeps waiting for the outcome of the budget discussions on the other side of the Atlantic. The U.S. House of Representatives and Senate want to restore most of LISA’s funding, but Mueller warns about the risks of Europe becoming complacent about the LISA partnership again.

“My biggest concern is if they say that they will do it and then pull out five years later,” Mueller said. “For LISA, that would be a huge disaster because at that point, everything would be going into flight hardware, everybody here has industrial contracts that we would have to continue to pay while trying to catch up on the hardware development that NASA should have provided.”

Mueller’s distrust of Europe’s collaboration with NASA is based on experience.

The LISA mission has been talked about among gravitational wave researchers for decades. In 1993, the project was included in ESA’s long-term plans, and in 1997, a partnership was formed between American and European scientists to work on the mission with a goal to launch around 2015. Then, in 2011, the partnership folded. The reason? NASA didn’t have the funds available to proceed with the construction within the required timeframe. Mueller was involved with the project already at that time and began calling for what he calls a “disentanglement” of all science space missions led by the two agencies.

“At that time, I already said that we should disentangle the agencies on the hardware and payload development side as much as possible to avoid funding issues in one agency from spilling over to the other agency,” Mueller said.

“People were massively against that at that stage.”

Mueller is concerned about the frequently changing funding priorities at NASA, which are not always due to turbulent politics. In fact, the 2011 withdrawal from LISA was prompted by NASA’s need to redirect funds into the construction of the flagship James Webb Space Telescope, which at that time had been dealing with major delays and cost overruns.

“It might happen again if, a few years from now, they run into cost overruns with the Habitable World’s Observatory, the new big NASA telescope project, and need to find the money somewhere,” said Mueller. “On the scientific side, it would be good for everyone to work together and have access to all the data. But the agencies should build the payloads and satellites separately.”

The Saga of the ExoMars Rosalind Franklin Rover

The poster child for ESA’s bad luck in international cooperation is the ExoMars Rosalind Franklin rover, Europe’s first robotic vehicle designed to search for traces of life on Mars. The rover is fitted with a 6-foot drill (2 meters) to access deeper layers of the Martian soil protected from life-destroying cosmic radiation that constantly batters the Red Planet’s surface. NASA is currently expected to provide a launcher, braking rocket engines for the rover’s landing platform and radio-isotope heaters to keep the rover warm in the frigid Martian night. This contribution, however, is also among the projects eliminated in the Trump budget proposal.

ESA expects NASA to fulfill its commitment, based on a letter received by the agency last month. If, however, NASA were to change its mind again, Rosalind Franklin, already delayed by ten years, would miss its 2028 launch window.

The ExoMars rover mission was already ditched by NASA once, in 2012, after budget cuts pressed by the Obama administration. ESA then turned to Russia, striking a deal with the ROSCOSMOS agency to provide a launcher, a landing platform, and few other pieces of technology with an aim to launch in 2018. Technical challenges led to a delay until 2022. Then, Russia invaded Ukraine, and ESA was forced to cut itself from its partner for political reasons just months before a scheduled launch date. As Europe was weighing its options, NASA stepped back in with an offer to help get ExoMars to the surface of Mars in 2028.

Lessons Learned?

Insider sources hinted that NASA’s original ExoMars betrayal prompted ESA to rethink its approach to future collaborations. Instead of the complete disentanglement favored by Mueller, the agency capped the contributions for its large missions by its non-European partners to 20%.

“They tried to put it at a level where they believe they can recover if the other partner drops out,” Mueller said. “This sounds like a smart move. For me, it's halfway. It only works if [the partners] drop out early enough. It can work up until the design review, but once you get to later stages, it would be much more expensive.”

According to available information, ESA expects to invest 1.75 billion Euros ($1.9 billion) into LISA. Individual European countries are making further contributions independent of the ESA budget.

According to one source, in the case of the cheaper medium-class missions, the European agency was at some point seeking to go it alone. When ESA selected the Ariel telescope (designed to study exoplanet atmospheres) in 2018, it deliberately kept NASA mostly out, according to the source. The U.S. agency is building one instrument for the mission — a spectroscope for studying clouds called CASE. The Trump administration wants to cancel funding for CASE, which might leave ESA with another hole to plug.

EnVision’s Radar

The story of how EnVision ended up with a US-made radar worth $100 million is somewhat murky. The mission was originally conceived with a British-made SAR instrument in mind, the source said, one based on a demonstrator built by Airbus for the UK-Australian NovaSAR-1 mission, which launched in 2018. Another source familiar with the discussions surrounding the conception of EnVision told Supercluster that the European community originally intended to keep NASA out of EnVision too, especially as it had been seen as a competitor to NASA’s own Venus missions DaVinci and Veritas.

Then, however, ESA member states didn’t agree on the funding for the radar development.

“The only reason the USA is in the EnVision mix, to my understanding, was because UK could not, or would not fund the radar and no one in Europe felt able or willing to take this on. So ESA went to NASA and appealed to them to join,” the source said.

The other source described the NASA-supplied radar as inferior to the one based on the NovaSAR mission, but said it was unlikely that technology would be brought back due to design changes to the spacecraft already made to accommodate the NASA-made VenSAR.

Support Supercluster

Your support makes the Astronaut Database and Launch Tracker possible, and keeps all Supercluster content free.

Support“[ESA] has been on a fact-finding effort to determine what could be supplied by European industry at short notice – though sadly it looks like the platform design is too far advanced to revert back to the original British VenSAR design,” said the source. “But certainly it seems that there are industry solutions available and that could be supplied within the restricted mission timeframe.”

An ESA representative told journalists at the agency’s recent ministerial conference that going forward, the agency would seek to develop mission technologies “on the critical path” in Europe.

Searching for New Purpose

ESA is still searching for a new purpose for several technologies developed for NASA-led missions, which have fallen victim to the American agency’s changing priorities. Before the Trump administration proposed to chop the Mars Sample Return mission altogether, NASA redesigned the mission’s architecture in 2022 in order to reduce cost.

At that time, NASA eliminated the sample collection rover developed in Europe in favor of a pair of cheaper quadcopters. ESA hopes the robotic arm, designed to pick up samples stored on the Martian surface by the Perseverance rover, might in the future find a new use, perhaps on one of the upcoming lunar missions.

The European agency was also building the return orbiter, intended to deliver those precious Martian samples to Earth. ESA’s Director of Human and Robotic Exploration Daniel Neuenschwander told journalists at the recent ministerial conference that ESA is now repurposing the return orbiter into a mission called ZefERO that would orbit Mars, study its geology and serve as a communications relay for rovers and landers on the planet's surface.

The Europe-made service module, which propels the Orion capsule intended to take humans to the Moon as part of the upcoming Artemis mission, will also be discontinued much sooner than ESA hoped for. The Trump administration intends to replace Orion and its launching rocket, the Space Launch System, with technology from commercial providers by the early 2030s.

Neuenschwander said ESA will study options to turn the service module into a multi-purpose space tug.

Regardless of the outcome of the discussions around NASA’s 2026 budget, the European space science and tech community will have some decisions to make about future collaborations.

For researchers like Mueller, the only other alternative to Europe going its separate way would be significant guarantees around the agencies’ mutual commitments.

“The alternative would be to really combine them at a much higher level,” said Mueller. “ But that seems to be impossible given their different rules and regulations around budget.”